This week we introduce you to the Negro League Centennial Team (1920 – 2020) which consists of 30 of the greatest African-American and Cuban players from 1895 – 1947.

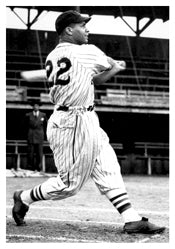

Today is one of the April releases – Biz Mackey wearing his Philadelphia Giants uniform.

From NLBemuseum.com -

“Biz Mackey was an incredibly talented receiver who remained cool under pressure, and his defensive skills were unsurpassed in the history of black baseball. Considered the master of defense, he possessed all the tools necessary behind the plate, but gained the most acclaim for his powerful and deadly accurate throwing arm. He could snap a throw to second from a squatting position and get it there harder, quicker, and with more accuracy than most catchers can standing up. Mackey delighted in throwing out the best base stealers, and his pegs to the keystone sack were frozen ropes passing the mound belt high and arriving on the bag feather soft.

Although he was barely literate, Mackey was intelligent, had a good baseball mind, and employed a studious approach to the game. The ballpark was his classroom, and inside baseball was his subject of expertise. He relied on meticulous observation and a retentive memory to match weaknesses of opposing hitters with the strengths of his pitching staff. An expert handler of pitchers, he also studied people and could direct the temperaments of his hurlers as well as he did their repertoires.

He was also a jokester, and utilized good-natured banter and irrelevant conversation to try to distract a hitter and break his concentration at the plate, and was a master at "stealing" strikes from umpires by framing and funneling pitches. Pitchers recognized his generalship and liked to pitch to the big, husky receiver who, for his size, was surprisingly agile behind the plate. This unexpected quickness, coupled with soft hands, enabled the versatile athlete to play often at shortstop, third base, or in the outfield, and although lacking noteworthy range, he proved adept at any position. He was also a smart base runner and, although not fast, pilfered his share of bases.

In his prime, the switch hitting Mackey was one of most dangerous hitters in baseball, with power from both sides of the plate, as evidenced by a .423 batting average, 20 home runs, and a .698 slugging percentage for Hilldale in the Eastern Colored League's inaugural season, 1923. Biz followed this campaign with averages of .337, .350, .327, .315, .327, .337, .400, and .376 for the years 1924-1931.

His competitive spirit led the Hilldale club to three successive pennants, capped by a victory over the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1925 Negro World Series. In that Series, in addition to his superior defensive talent, he further displayed his batting skills, leading the team with a .375 average.

The big Texan learned the rudiments of baseball in the Lone Star State and, at age eighteen, began playing with his two brothers on a Prairie League baseball team in his hometown of Luling, Texas. After two years he began playing professionally with the San Antonio Black Aces in 1918. Financial problems plagued the ownership, and the team folded in 1920, but Mackey and several of the other top players were ready for the big time and were sold to the Indianapolis ABC's in time for the Negro League's inaugural season. Initially he served as a utility man, playing a variety of positions while learning the craft of baseball under manager C.I. Taylor, a master teacher. In his three seasons with the ABCs he batted .306, .296, and .361 and had slugging percentages of .558 and .630 the latter two seasons. When the Eastern Colored League was organized in 1923, the owners raided the Negro National League for players, and Mackey was one of the plums picked by Hilldale owner Ed Bolden.

In his first two seasons with the club, he split his playing time between catching and shortstop, sharing duties behind the plate with aging superstar Louis Santop. But for the championship 1925 season he won the position full time, and for the next decade retained recognition as the premier receiver in black baseball.

Mackey was in demand for postseason exhibitions and played against major league all star squads in Baltimore (including a 1926 series when Hilldale won 5 of 6 games from the Philadelphia Athletics with Lefty Grove) until the weather dictated a halt to the contests, after which he would travel to the West Coast for the California winter league. Playing with the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1921 22, he hit for a lusty .382 average, and against a team headed by the Meusel brothers, Bob and Irish, rapped the ball at a .341 clip as the black stars annexed 7 victories in the 11 game series.

His barnstorming almost led to his banishment from the Negro Leagues, when in the early spring of 1927, despite warnings of a possible lifetime expulsion from angry league owners, he signed with an all star team embarking on a baseball tour to Japan. Although he missed most of the season, the peerless receiver was welcomed upon his return, and stepped right back into the clean- up slot for Hilldale. After the regular season ended, he played with the Homestead Grays in postseason games.

In the Orient, the black Americans were immensely successful, both as diamond favorites and as diplomats. They lost only a single ball game, and their shadow ball routines and exhibitions of baseball skills delighted the fans and are credited as the catalyst for the organization of the Japanese professional leagues a decade later. Mackey, who was especially popular with the Japanese, made two more trips to the Land of the Rising Sun, in 1934 35, after he had joined Ed Bolden's new team, the Philadelphia Stars.

Mackey teamed with the Stars' young left-handed fireballer, Slim Jones to form a superb battery, and together they provided the impetus for the Stars' 1934 drive to win the Negro National League pennant with a come from behind victory over the Chicago American Giants in the 7 game league championship series.

In balloting for the inaugural East-West All Star game in 1933, Mackey's all around skills were preferred over the slugging ability of young Josh Gibson. Mackey was then thirty-six years old and past his prime, while Gibson was just beginning to hit his full stride. However, Mackey's defensive skills were still so far above those of other catchers that he played in four of the first six midsummer classics.

Even as late as 1937, when he was managing the Baltimore Elite Giants, he was still considered the best all around receiver in the Negro Leagues. One of his proteges with the Elites was Roy Campanella, who credits Mackey with teaching him the finer points of catching. Observers say that watching Campanella was like seeing Mackey behind the plate again.

In 1939 Mackey relinquished the managerial reins to George Scales and joined the Newark Eagles, where he continued his work grooming young players. Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Don Newcombe were all beneficiaries of the Mackey touch during his stint as player manager at Newark. Toward the end of his thirty-year career he directed the Eagles to the 1946 Negro world championship with a victory over the Kansas City Monarchs in the World Series.

Even then, Mackey was a formidable player, showing a .307 batting average for 1945 and receiving a free pass in a pinch hitting appearance in the 1947 All Star game at age fifty. Mackey, a non-smoker and non-drinker, was an exemplary role model for young players and was still managing the Eagles in 1950, after a change in ownership had resulted in the franchise being moved to Houston, in his native state.

After retiring from baseball, he lived in Los Angeles and ran a forklift. He was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

The smooth-operating receiver finished his career with a lifetime average of .335 in league play and an average of .326 against major-league competition in exhibition games. Biz's tremendous hitting, coupled with his sterling defensive skills, leaves no doubt that he was one of the true greats at his position.”

About the Bobblehead:

Each individual will be depicted on a baseball-shaped base with replica of Kansas City’s Paseo YMCA, the site where the Negro National League was organized on February 13, 1920.

The bobbleheads are officially licensed by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and approved by the families when applicable.

- An average of two bobbleheads per month will be released from January 2019 through February 2020

- Bobbleheads are high quality and produced by the National Bobblehead Hall of Fame and Museum

- Individually numbered to only 2,020

#HistoryInYourSize

Learn more about the NLBM and shop Hilldale Giants shirts today!